In the last month of her pregnancy, Lisa LeViere sometimes had four medical appointments in a week, which meant more than four hours in the car, if traffic was clear.

A resident of Portersville in Butler County, LeViere, 33, had a weekly checkup with her obstetrician in Butler. It was a 30-minute drive each way. Because of gestational diabetes, she also had to report twice a week for a fetal non-stress test.

The high-risk aspects of her pregnancy made it necessary for her to further add in hour-and-a-half round trips to see maternal-fetal medicine specialists at the Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC in Pittsburgh.

LeViere’s husband is often out of town for his work as a demolition coordinator. Their three other kids, ages 2 to 5, stayed with his retired mother while LeViere shuttled back and forth. “If we didn’t have family here, I don’t know what I would have done,” she said.

More women in Pennsylvania are making these kinds of journeys for pregnancy care and delivery. According to the state Department of Health’s annual hospital survey, from 2004 to 2014, the commonwealth lost 28 obstetric units — colloquially known as maternity wards or delivery rooms — from a total of 124 units, a 23-percent decline.

The closures first hit urban centers and were mostly spurred by the consolidation of medical centers under a few healthcare networks, but the decline has branched out to suburban and rural areas, stranding women like LeViere miles away from one-stop locations for comprehensive care.

Ellwood City Hospital, the one nearest to the LeVieres at about 10 miles away, closed its obstetric unit in 2013. It was costing the hospital $200,000 a year. Another two nearby, the Grove City Medical Center and Jameson Hospital in New Castle, shuttered obstetric units for financial and staffing reasons in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

From Northern Allegheny County to Erie, a stretch that ranges from residential to rural, there is no hospital with an obstetric unit, according to the latest health department survey. In some parts of central Pennsylvania, there isn’t one in a 50-mile radius, said Lisa Davis, director of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health at Pennsylvania State University.

Studies have correlated distance to obstetric services to poor medical outcomes, and access to obstetric care is on the decline across the United States, particularly outside of metropolitan centers.

A study released in January from the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center found about 7 percent of rural hospitals closed obstetric units between 2010 and 2014. “With each new closure, the nearest hospital that offers obstetric care is getting farther and farther away,” said Katy Kozhimannil, one of the authors of the study.

The high cost of low birth rates

There are multiple reasons for the decline.

Obstetric units are expensive. Like an intensive care unit, they require costly equipment and around-the-clock staffing. “For obstetrics, you have to be ready all the time,” said Kozhimannil.

It can also be difficult for rural areas to keep doctors. In another study, Kozhimannil and coauthors found that, of 306 rural U.S. hospitals surveyed, 28 reported decreases in obstetricians and 24 reported decreases in family physicians who tend to deliveries. Nearly all, 98 percent, “reported challenges in staffing.”

Also, the insurance rates for obstetric surge past those of other medical specialties, Davis said. “For any hospital, labor and delivery services have high medical malpractice rates,” she said. “If there are complications or injury to a newborn, the damages can be very high.”

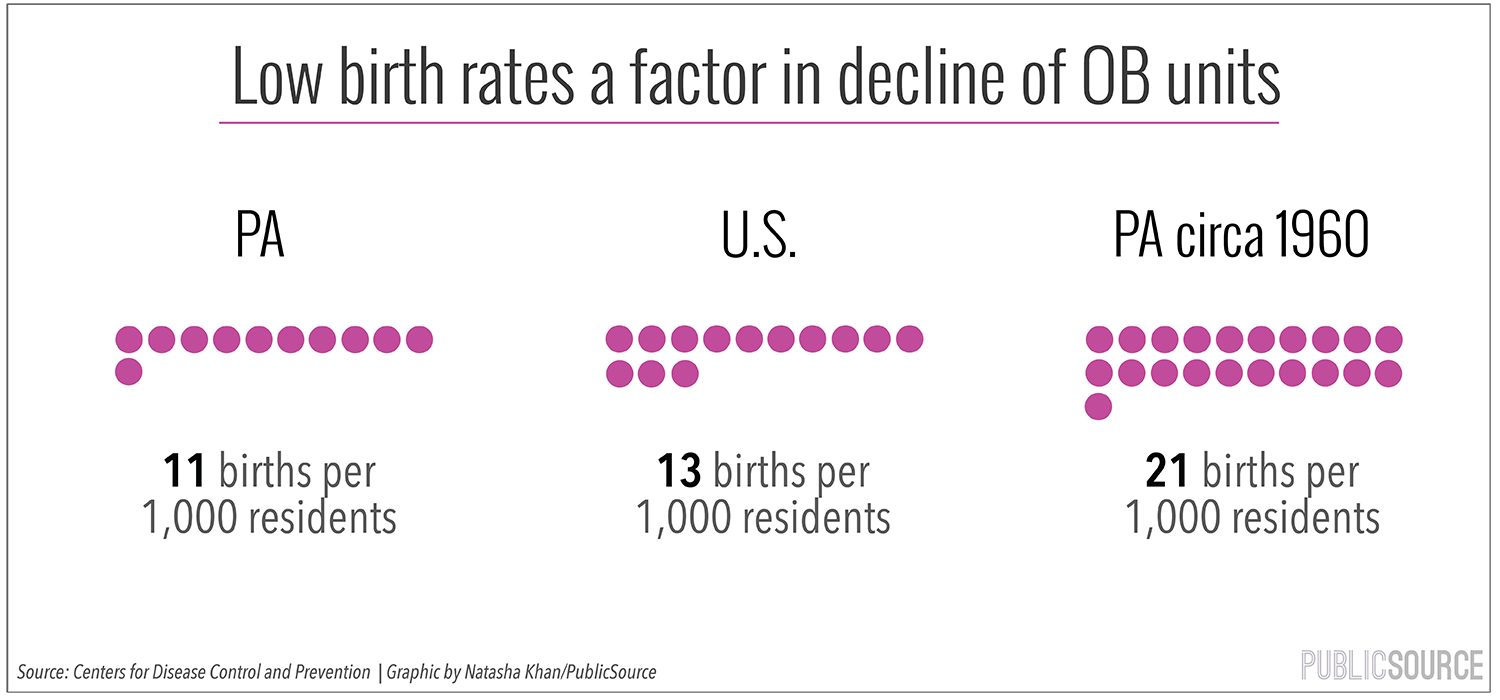

Low birth rates are another factor, Kozhimannil said.

Although the birth rates has been consistent in recent years, they’ve been declining in the United States for decades, and Pennsylvania’s is particularly low. The state’s rate is 11 births per 1,000 residents per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control, lower than the national average of 13. In 1960, there were 21 births per 1,000 residents.

To put it in financial terms, the customer base for obstetric care is shrinking.

This decline in obstetric [OB] units has medical consequences. A 2011 study from Canada, which is experiencing a similar trend, found higher rates of infant intensive care admissions for mothers one to two hours away from obstetric services. This matches findings from a 1990 study in the state of Washington that correlated distances to care to complicated deliveries, prematurity and higher costs of neonatal care.

“We know that distance does have an impact on outcome, though we don’t have an exact measure of what distance means what outcomes,” Kozhimannil said. “What to expect at 30 miles? 60 miles? 90 miles? We don’t know yet, but we do know there are consequences.”

Cities also have fewer obstetric units than they did in the past, but the consequences might be less severe. A study in the journal Health Services Research examined effects of a loss of OB units in Philadelphia from 1995 to 2005, due to health networks consolidating services to a few hospitals, and found there was no significant change in any long-term outcome.

For women outside cities, Kozhimannil said medical appointments suck up more time and money. Patients are more likely to miss them because of work or the lack of childcare or transportation. That leaves their doctors with fewer opportunities to detect or treat issues.

Searching for options

The distance to care has caused some expectant Pennsylvanians to exit the hospital system altogether. In 1998, 3,285 state births occurred outside a hospital, most under the watch of a midwife. By 2013, that number had surged to 4,551, according to the state Department of Health.

Kristin von Hofen, 26, and her husband David, 31, live in Carlton in Crawford County, along that obstetrically depleted stretch from Pittsburgh to Erie.

During their first pregnancy last year, they determined their nearest workable option was 55 miles away in Erie. “Thus, after careful and thoughtful consideration we looked into midwifery and home birthing,” Kristin wrote in an email. They hired a midwife who usually caters to Amish and Mennonite parents, though the von Hofens are neither.

She came to their home regularly and monitored Kristin’s and the baby’s conditions, eliminating the need for a commute. Their son, Dawson, was born in the bedroom he’d soon inhabit, without complication, under the watch of the midwife and a doula. The whole package cost $2,000, and they did not use insurance.

This isn’t an option for everyone. Kristin von Hofen was a candidate because initial visits to Saint Vincent Hospital in Erie determined that her pregnancy was low risk.

Lisa LeViere, whose pregnancy was complicated, delivered her daughter Elizabeth on March 17 at Butler Memorial Hospital. It doesn’t have an OB unit, but her obstetrician has admitting privileges. Her options were not what she hoped.

Her obstetrician would not perform a VBAC (vaginal birth after cesarean) there, and she labored with the fear that complications from gestational diabetes would mean the baby would need to be transported to a neonatal intensive care unit in Pittsburgh, while she would be stuck in Butler recovering from the cesarean.

To deliver more comprehensive care outside of cities, experts do have public policy suggestions.

Davis, of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health, suggests restructuring Medicaid to fund some hospitals for critical services on an ongoing basis, as opposed to compensating them per patient after care has been rendered.

Kozhimannil also suggests student loan forgiveness for obstetricians and other labor and delivery professionals who relocate to remote areas.

Health network solutions

Hospitals and physician groups increasingly fall under the umbrellas of large networks. In many cases, they’ve reorientated the flow of obstetric care to a few facilities.

UPMC, which now claims to control 41 percent of the medical-surgical market in Western Pennsylvania, “strategically consolidated some of [its] OB units,” in the last 20 years, according to Maribeth McLaughlin, vice president of patient care services at Magee-Womens Hospital. This included units in McKeesport, McCandless and Pittsburgh’s Shadyside neighborhood.

McLaughlin touts the system’s increased focuses on new methods, like prenatal care in outpatient facilities through the use of telemedicine.

In one case, the dearth of obstetric care and competition led to one network seeing an opportunity.

In 2013, unable to resolve contract disputes with UMPC, the insurer Highmark formed its own provider network Allegheny Health Network [AHN], purchasing a few hospitals. One of its priorities was investing in women’s health care, said founding CEO John Paul.

In studying areas for improvement, executives realized 90 percent of the pregnant women in the coverage area of AHN’s Jefferson Medical Center in Clairton were commuting to Pittsburgh.

Monongahela Valley Hospital stopped delivering babies in 2007.

Six years later, 3,600 pregnant women along the Route 51 corridor were going to Pittsburgh — some of them into the delivery rooms of AHN’s main competitor, UPMC.

In November 2014, Jefferson Medical Center opened the first new obstetric unit in Pennsylvania in 35 years. The unit was designed as a one-stop destination for delivery and the medical care leading up to it. AHN predicted 500 births in the first year. They had 670.

Dr. Allan Klapper, system chair of obstetrics and gynecology, said there are “many layers” to the problem of obstetric unit closures. The specialty is usually not profitable, he said, but patients should demand health networks invest in it from more lucrative services.

He said he is certain the Jefferson unit’s triage team saved infant lives that would have been lost if the women were transferred to Pittsburgh. “We have had moms go into labor early and when we looked at the fetal heart rate, the baby had to be delivered immediately,” Klapper said.

“Delivery situations are often emergency situations,” he added. “Can you imagine having to travel so many miles for an ER. Of course, that would cost lives.”

Nick Keppler is a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer who has written for Vice, Nerve, and the Village Voice. Reach him at nickkeppler@yahoo.com.

The Jewish Healthcare Foundation has contributed funding to PublicSource’s healthcare reporting.