I am an only child, made up truly of equal parts my father and my mother.

I have my mother’s sense of introspection and trepidation, and I have my father’s creativity balanced by his analytical mind. In culmination, it creates a balance that can quickly teeter into neuroses, but my father has always kept me as upright as he could. He is my beacon whenever the tide starts to rip me away from the shore.

There had always been a silent understanding between us. It was understood over sushi or tacos. It reverberated between us while we walked the aisles of a comic con or while building scale models or painting. It made the air feel different on a movie night. It made family functions bearable — that inside joke, that smirk at the dinner table, that thing that gave every tough situation levity. That knowing. Knowing that I had a father who believed in every single thing about me, who valued every single thing about me.

When he died, parts of who I am felt like they’d disappeared — like I’d been re-arranged on an atomic level; shifted around and reconfigured in the wake of his loss. I spent months sitting at his workbench, picking up tiny pieces to the model boat he’d been building, inspecting them, imagining his hands working on them, and then putting them back down, carefully, exactly where he’d left them last. The closest I could feel to him felt foggy at best, like a half-drunk memory — the wisp of his presence but never him.

That knowing was still there, though. That silent understanding. That belief he had in me. That was what he left behind for me. Instilled deep into my heart, it’s the only thing that kept me upright.

Exactly a month after his passing, I felt a quiver in my belly and a seasickness in my head. I’d be a first-time mother just eight months later to a son my father would never meet.

As my belly grew, so did my grief. Losing my father and gaining my son felt like an exchange, and in my despair, I couldn’t understand why I hadn’t been allowed to have both. The pregnancy felt like a gift in a time of darkness, but it also felt like a cruel joke that I couldn’t share it with my dad. There was a surrealism that draped itself over my life no matter where I walked. The grocery store, the beach on vacation, the sidewalk with my dogs, even pacing my own house. I was a woman in between, unable to fully feel the deepest sadness of my life or the greatest elation of my life.

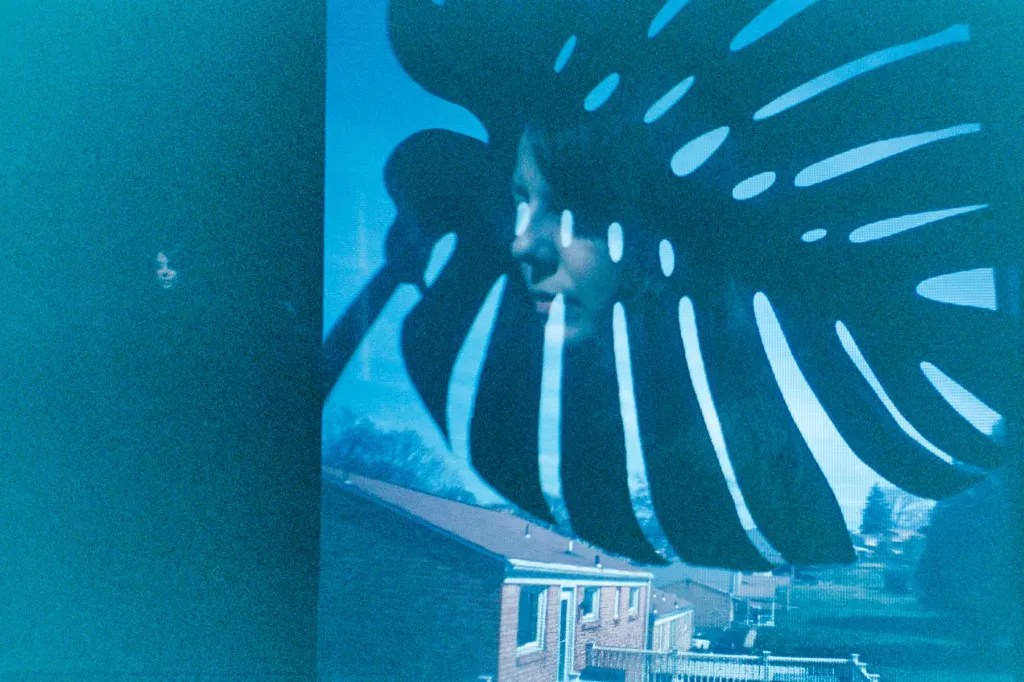

“We are held.” Author Amanda Filippelli’s one-year-old son, River, plays with her hands, Tuesday, March 21, 2023, in Baldwin. At right, Amanda stands by her house for a portrait. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

I was so excited about being pregnant. Waves of a new kind of love — a deeply unmatched sort of love — washed over me in swells that sometimes took away the sadness in my heart, but I was caught in between both. Battered in a storm of warring emotions, I had to make a decision before my son was born. I had to make a decision that I wasn’t going to be a sad mom. That I wasn’t going to be so conflicted. That I wouldn’t grow him in a womb full of grief, and that I wouldn’t raise him as a mother full of sadness.

I tried to peek from behind the veil of grief and look at life differently, change my perspective. When you lose someone, everyone tells you they’re in the birds and in ladybugs and dragonflies and hummingbirds, or that they’re dropping pennies on the ground and dimes in socks for you to find. I couldn’t see my dad in any of those things.

Photos from author Amanda Filippelli’s Baldwin home, Tuesday, March 21, 2023, including some multiple exposures on film. Pictured at top is a 1988 family photo of Amanda with her late father on a visit to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and a 2014 photo of Amanda’s parents at her wedding in Hawaii. (Photos by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

We rented a cabin on a mountainside in the white-blue of January. It was quiet and the snowfall was serene at such a high elevation. We were so close to the clouds that the flakes came down slowly, not yet caught up in the windfall. I closed my coat over my belly, tugged the zipper with a little force over the roundness, and started out for a walk about the property. When I said I wanted to be alone, my husband reminded me to watch my step, take it slow, don’t be out too long — all the things everyone suddenly says to you when you’re pregnant.

It would’ve been easy to go snowblind if it hadn’t been for all the boulders as tall as my neck lining the trail. I liked the way the glare of the blanketed forest made me feel — light and hidden and whimsical — all while rubbing my hands over the kicks in my belly. We came upon a frozen pond and stopped to admire the stillness of the scene. There were purple veins in the ice, cracks that had frozen over again and again. The surface beneath was dotted and blotchy with all the life that was suspended there, waiting for the sun to warm the pond back into motion. I thought I could see the universe in there. Constellations, at least. And in the same moment, the stillness made me shudder, made me think of finding my dad, lifeless, made me feel stuck again. As quickly as I started to sink into that familiar feeling, something new came over me. Something different. Something as shocking as the sting of ice-cold air. I felt hope, like there is more beneath the surface of this life than we can see, and I heard myself say to my son, “We are held,” without knowing why I said it but also knowing exactly what it meant.

I still say it to him and to myself now.

We are held.

And in that moment, I understood why people want to see their dead in the birds and in ladybugs and pennies, because I could feel my dad there, with us, in the icy depth of that pond, and I felt at ease for the first time in a long time.

Months later, I found myself in the hospital because I was past my due date. They show me that I am in labor, probably have been for a while. The contractions make tall spikes on the monitor and they’re happening all of the time, but I can’t feel them much at all. I learn that my body refuses to open, even though I’ve so intentionally prepared for this moment. We talk a lot about dilation and how we’re going to force it, and when the time comes to make myself a portal, I realize my body has clammed up, has shut itself up, maybe because letting my son out feels like letting go all over again.

I take a deep breath, think about the icy stillness of water in the wintertime, and whisper to my son, “We are held,” and he comes rushing into the world.

Amanda Filippelli is a writer, editor, book coach and artist. Her latest book of poetry and prose, “The Remembering Room,” has been interpreted into a free interactive art installation that helps people process grief and find connection. You can visit the exhibit at Atithi Studios in Pittsburgh through April 16, 2023. To learn more or get in touch with Amanda, please visit AmandaFilippelli.com.